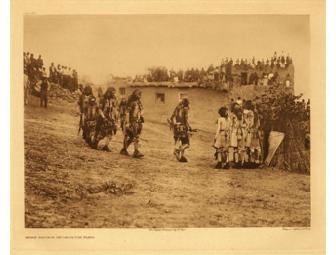

Framed Vintage Photogravure by Edward S. Curtis; Snake Dancers

Item Number: 143

Time Left: CLOSED

Value: $1,550

Online Close: Jun 7, 2010 4:30 PM PDT

Bid History: 0 bids

Description

Etherton Gallery

135 s. 6th Ave.

Tucson, AZ 85701

520-624-7370

www.ethertongallery.com

Framed vintage photogravure

by Edward S. Curtis:

Snake Dancers Entering the Plaza,

1921, plate 422.

The North American Indian, Portfolio 12.

Etherton Galley is proud to be celebrating 29 years of showing the best in vintage, classic and contemporary photography. Recently named Best Art Gallery in Tucson by The Tucson Weekly, the gallery proudly shows a variety of local artists in all media as well as photography. Located upstairs in the historic Odd Fellows Hall at 135 S. 6th Ave.

Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868-1952)

Edward S. Curtis was born near Whitewater, Wisconsin. His father, a Civil War veteran and minister, moved the family to Minnesota, where Edward became interested in photography. In 1892 Curtis purchased an interest in a photographic studio in Seattle. He married and the couple had four children. He later settled in Los Angeles, where he operated photographic studios at various times on La Cienega Boulevard and in the Biltmore Hotel. As a friend of Hollywood producer Cecil B. DeMille, Curtis was commissioned to make film stills of some of DeMille's films, including the epic, The Ten Commandments. In 1899, he became the official photographer for the Edward Harriman expedition to Alaska and developed an interest Native American culture.

Curtis is best known for his documentation of Native American cultures published as The North American Indian. From about 1900 to 1930 he surveyed more than 100 tribes ranging from the Inuits to the Hopi, making more than 40,000 photographs. He made portraits of important and well-known figures of the time, including Geronimo, Chief Joseph, Red Cloud, and Medicine Crow.

Curtis’ project was time consuming and complex, because he needed vehicles, mechanical equipment, skilled technicians, scholars and researchers and the cooperation of the Indian tribes. His working method was to dispatch assistants to make tribal visits months in advance. Curtis then traveled by horseback or horse drawn wagon to visit the tribes. Once on site Curtis and his assistants interviewed the people and then photographed them outside, in an indigenous structure, or inside his studio tent with an adjustable skylight.

Curtis used a field or view camera, producing his images on glass plates. He developed his images in the field, then created a proof from each image, and sent it, with instructions, back to his Seattle studio where manager Adolph Muhr made decisions related to exposure time, retouching, and enlargement. The North American Indian consisted of 20 bound volumes containing approximately 2200 photogravures, written information about the Native American cultures he photographed and 20 supplementary photogravure portfolios. Each volume was devoted to a single or sometimes multiple groups. The photogravures were hand-pulled from a steel-coated copper plate and then printed on one of three types of paper; a rice paper called vellum, a heavier water-marked paper known as Van Gelder and Japon tissue (mounted on vellum). Each volume was bound in leather and edged in gilt. In addition to the published volumes, Curtis’ output also included gelatin silver prints, platinum prints and orotones, such as At The Old Well at Acoma (1906).

Curtis intended to record Native American culture which was disappearing in the face of encroaching modern civilization. However, to preserve these vanishing native cultures, he constructed his portraits using “authentic” costumes, props, and staged ceremonies. Occasionally he used the incorrect cultural artifacts and costumes to document a particular tribe. Ironically, Curtis believed that the only way that Native Americans could survive was through assimilation. The last volume of The North American Indian was published in 1930. Although accounts vary, about 272 sets were sold. Eventually his 30-year project took its toll. Curtis’ wife divorced him, and later he suffered a physical and nervous break down. Declining interest in the American Indian and the Depression ultimately reduced sales. Curtis spent the remaining years of his life with his daughter Beth and her husband in Los Angeles. In 1952 Curtis died in Los Angeles, virtually unknown. Fortunately, Curtis’ work was discovered in the late 1970s-1980s. His work is in several major public collections including the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian and several major universities.

Sources: The Center for Creative Photography, the J. Paul Getty Museum, The Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division and the Public Broadcasting Service

Special Instructions

Auction winner must pick up at KXCI studios or pay for shipping.