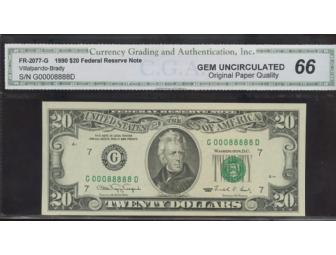

$20 1990 CHICAGO GD BLOCK CGA 66 OPQ LUCKY SERIAL 88888

Item Number: 237

Time Left: CLOSED

Value: $6,000

Online Close: Oct 30, 2010 7:00 PM EDT

Bid History: 0 bids

Description

Ownership of this jewel should equal the impact of all your childhood christmases combined at the same exact moment. One might wish to wear sunglasses when viewing this headlight, as a glance may be akin to looking at the Dragon, or directly into the eye of Buddah.

A Federal Reserve Note (FRNs or ferns, not to be confused with "Federal Reserve Bank Note") is a type of banknote issued by the Federal Reserve System and is the only type of American banknotes that still circulates today.

Federal Reserve Notes are fiat currency, with the words "this note is legal tender for all debts, public and private" printed on each bill. (See generally 31 U.S.C. § 5103.) They are issued by the Federal Reserve Banks and have replaced United States Notes, which were once issued by the Treasury Department.

The paper that Federal Reserve Notes are printed on is made by the Crane Paper Company of Dalton, Massachusetts.

The first institution with responsibilities of a central bank in the U.S. was the First Bank of the United States, chartered in 1791 by Alexander Hamilton. Its charter was not renewed in 1811. In 1816, the Second Bank of the United States was chartered; its charter was not renewed in 1836, after it became the object of a major attack by president Andrew Jackson. From 1837 to 1862, in the Free Banking Era there was no formal central bank. From 1862 to 1913, a system of national banks was instituted by the 1863 National Banking Act. A series of bank panics, in 1873, 1893, and 1907 provided strong demand for the creation of a centralized banking system. The first printed notes were Series 1914.

The authority of the Federal Reserve Banks to issue notes comes from the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Legally, they are liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks and obligations of the United States government. Although not issued by the Treasury Department, Federal Reserve Notes carry the (engraved) signature of the Treasurer of the United States and the United States Secretary of the Treasury.

Federal Reserve Notes are fiat currency, which means that the government is not obligated to give the holder of a note gold, silver, or any specific tangible commodity in exchange for the note. Before 1971, the notes were "backed" by gold: that is, the law provided that holders of Federal Reserve notes could exchange them on demand for a fixed amount of gold (though from 1934–1971 only foreign holders of the notes could exchange the notes on demand). Since 1971, federal reserve notes have not been backed by any specific asset. While 12 U.S.C. § 411 states that "Federal Reserve Notes . . . shall be redeemed in lawful money on demand" this means only that Federal Reserve banks will exchange the notes on demand for new Federal Reserve notes. Thus today the notes are backed only by the "full faith and credit of the U.S. government"—the government's ability to levy taxes to pay its debts. In another sense, because the notes are legal tender, they are "backed" by all the goods and services in the economy; they have value because the public accepts them in exchange for valued goods and services. Intrinsically they are worth the value of their ink and paper components.

Federal Reserve Notes are printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP), a bureau of the Department of the Treasury. The Federal Reserve Banks pay the BEP only the cost of printing the notes (about 4¢ a note), but to circulate the note as new currency rather than merely replacing worn notes, they must pledge collateral for the face value, primarily in Federal securities.

Federal Reserve notes, on average, remain in circulation for the following periods of time:

$1 | 21 months |

$5 | 16 months |

$10 | 18 months |

$20 | 24 months |

$50 | 55 months |

$100 | 89 months |

The Federal Reserve does not publish an average life span for the $2 bill. This is likely due to the fact that it is treated as a collector's item by the general public, and therefore is not subjected to normal circulation.

In contrast, the Federal Reserve pays the United States Mint—another Treasury bureau—face value for coins, as coins are direct obligations of the Treasury.

A commercial bank that maintains a reserve account with the Federal Reserve can obtain notes from the Federal Reserve Bank in its district whenever it wishes. The bank must pay for the notes in full, dollar for dollar, by debiting (drawing down) its reserve account. Smaller banks without a reserve account at the Federal Reserve can maintain their reserve accounts at larger "correspondent banks" which themselves maintain reserve accounts with the Federal Reserve.

U.S. paper currency has had many nicknames and slang terms, some of which ("sawbuck" and "double-sawbuck") are now obsolete. The notes themselves are generally referred to as bills (as in "five-dollar bill") and any combination of U.S. notes and coins as bucks (as in "fifty bucks").

See tables below for nicknames for individual denomination

- Greenbacks, any amount in any denomination of Federal Reserve Note (from the green ink used on the back)

- Dead presidents, any amount in any denomination of Federal Reserve Note (from the portrait of a U.S. president on most denominations)

- One hundred dollar bills are sometimes called "Benjamins" (in reference to their portrait of Benjamin Franklin) or C-Notes (the letter "C" stands for the Roman Numeral 100).

- One thousand dollars ($1000) can be referenced as "Large", "K", "Grand" or "Stack", and as a "G" (short for "grand").

Many more slang terms refer to money in general (moolah, paper, cash, etc.).

Despite the relatively late addition of color and other anti-counterfeiting features to U.S. currency, critics hold that it is still a straightforward matter to counterfeit these bills. They point out that the ability to reproduce color images is well within the capabilities of modern color printers, most of which are affordable to many consumers. These critics suggest that the Federal Reserve should incorporate holographic features, as are used in most other major currencies, such as the pound sterling, Canadian dollar and euro banknotes, which are more difficult and expensive to forge. Another robust technology, the polymer banknote, has been developed for the Australian dollar and adopted for the New Zealand dollar, Romanian leu, Thai baht, Papua New Guinea kina and other circulating, as well as commemorative, banknotes of a number of other countries. Polymer banknotes are a deterrent to the counterfeiter, as they are much more difficult and time consuming to reproduce. They are more secure, cleaner and more durable than paper notes.

However, U.S. currency may not be as vulnerable as it is said to be. Two of the most critical anti-counterfeiting features of U.S. currency are the paper and the ink. The exact composition of the paper is confidential, as is the formula for the ink. The ink and paper combine to create a distinct texture, particularly as the currency is circulated. The paper and the ink alone have no effect on the value of the dollar until post print. These characteristics can be hard to duplicate without the proper equipment and materials.

The differing sizes of other nations' banknotes are a security feature that eliminates one form of counterfeiting to which U.S. currency is prone: Counterfeiters can simply bleach the ink off a low-denomination note, typically a single dollar, and reprint it as a higher-value note, such as a $100 bill. To counter this, the U.S. government has included a vertical strip imprinted with denominational information, and has considered making lower-denomination notes slightly smaller than those of higher denomination. Current proposals suggest making the $1 and $5 bills an inch shorter in length and a half-inch shorter in height

Critics also note that U.S. bills are often hard to tell apart: they use very similar designs, they are printed in the same colors (until the 2003 banknotes), and they are all the same size. Advocates for the blind have argued that American paper currency design should use increasing sizes according to value and/or raised or indented features to make the currency more usable by the vision-impaired, since the denominations cannot currently be distinguished from one another non-visually. Use of Braille codes on currency is not considered a desirable solution because (1) these markings would only be useful to people who know how to read braille, and (2) one braille symbol can become confused with another if even one bump is rubbed off. Though some blind individuals say that they have no problems keeping track of their currency because they fold their bills in different ways or keep them in different places in their wallets, they nevertheless must rely on sighted people or currency-reading machines to determine the value of each bill before filing it away using the system of their choice. This means that no matter how organized they are, blind Americans still have to trust sighted people or machines each time they receive change for their purchases or each time they receive cash from their customers. Nor does this help blind or partially sighted tourists.

By contrast, other major currencies, such as the pound sterling and euro, feature notes of differing sizes: the size of the note increases with the denomination and are printed in different colors. This is useful not only for the vision-impaired; they nearly eliminate the risk that, for example, someone might fail to notice a high-value note among low-value ones. Tourists also frequently encounter difficulties with U.S. money, as they are less familiar with the design cues that distinguish the various denominations.

Multiple currency sizes were considered for U.S. currency, but makers of vending machines and change machines successfully argued that implementing such a wide range of sizes would greatly increase the cost and complexity of such machines. Similar arguments were unsuccessfully made in Europe prior to the introduction of multiple note sizes.

Alongside the contrasting colors and increasing sizes, many other countries' currencies contain tactile features missing from U.S. banknotes to assist the blind. For example, Canadian banknotes have a series of raised dots (not Braille) in the upper right corner to indicate denomination. Mexican peso banknotes also have raised patterns of dashed lines.

On November 28, 2006, U.S. District Judge James Robertson ruled that the American bills gave an undue burden to the blind and denied them "meaningful access" to the U.S. currency system.

Ruling on a lawsuit filed in 2002 by the American Council of the Blind, Judge Robertson accepted the plaintiff's argument that current practice violates Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. (Ruling as PDF file) The Treasury is appealing the decision. The judge has ordered the Treasury Department to begin working on a redesign within 30 days.

The plaintiff's attorney was quoted as saying "It's just frankly unfair that blind people should have to rely on the good faith of people they have never met in knowing whether they've been given the correct change."

Government attorneys estimated that the cost of such a change ranges from $75 million in equipment upgrades and $9 million annual expenses for punching holes in bills to $178 million in one-time charges and $50 million annual expenses for printing bills of varying sizes.

On May 20, 2008, in a 2-to-1 decision, the U.S. Court of District Appeals for the D.C. Circuit upheld the earlier ruling, pointing out that the cost estimates were inflated and that the burdens on blind and visually impaired currency users had not been adequately addressed.

Shipping: FREE