4 VIP Admission Passes to DeYoung or Legion of Honor

Item Number: 279

Time Left: CLOSED

Description

Nod to the bouncer, cut the line and sashay in like a big shot with 4 VIP Admission Passes to DeYoung or Legion of Honor.

History of the de Young Museum

The de Young Museum originated as the Fine Arts Building, which was constructed in Golden Gate Park for the California Midwinter International Exposition in 1894. The chair of the exposition organizing committee was Michael H. de Young, co-founder of the San Francisco Chronicle. The Fine Arts Building was designed in a pseudo–Egyptian Revival style and decoratively adorned with images of Hathor, the cow goddess. Following the exposition, the building was designated as a museum for the people of San Francisco. Over the years, the de Young has grown from an attraction originally designed to temporarily house an eclectic collection of exotic oddities and curiosities to the foremost museum in the western United States concentrating on American art, international textile arts and costumes, and art of the ancient Americas, Oceania and Africa.

The new Memorial Museum was a success from its opening on March 24, 1895. No admission was charged, and most of what was on display had been acquired from the exhibits at the exposition. Eleven years after the museum opened, the great earthquake of 1906 caused significant damage to the Midwinter Fair building, forcing a year-and-a-half closure for repairs.

Before long, the museum's steady development called for a new space to better serve its growing audiences. Michael de Young responded by planning the building that would serve as the core of the de Young Museum facility through the 20th century. Louis Christian Mulgardt, the coordinator for architecture for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition, designed the Spanish-Plateresque-style building. It was completed in 1919 and formally transferred by de Young to the city's park commissioners. In 1921, de Young added a central section, together with the tower that would become the museum's signature feature, and the museum began to assume the basic configuration that it retained until 2001. Michael de Young's great efforts were honored with the changing of the museum's name to the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum. Yet another addition, a west wing, was completed in 1925, the year de Young died. Just four years later, the original Egyptian-style building was declared unsafe and demolished. By the end of the 1940s, the elaborate cast concrete ornamentation of the original de Young was determined to be a hazard and removed because the salt air from the Pacific had rusted the supporting steel.

In the mid-1960s, following Avery Brundage’s bequest of his magnificent Asian art collection, the Brundage wing was constructed, thereafter altering the museum’s orientation toward the Japanese Tea Garden, another remnant of the 1894 Midwinter Fair. In 1994 city voters overwhelmingly supported a bond measure to renovate the former San Francisco Main Library as the new home of the Asian Art Museum. Architect Gae Aulenti—widely recognized for adapting historic structures into museum spaces—was chosen as the design architect for the new facility. The Asian art collection remained open to the public at the de Young until October 2001, when it closed in preparation for the move. In November 2003 it re-opened its doors to the public at its new Civic Center location as an independent museum.

In 1989 the de Young suffered significant structural damage as a result of the Loma Prieta earthquake. The Fine Arts Museums' board of trustees completed a project that braced the museum as a temporary measure until a long-term solution could be implemented. For the next several years, the board actively sought solutions to the de Young's structural jeopardy and solicited feedback from throughout the community, conducting numerous visitor surveys and public workshops.

With extensive public input, the board initiated a process to plan and build a privately financed institution as a philanthropic gift to the city, in the tradition of M. H. de Young. An open architectural selection process took place from 1998 to 1999. The board endorsed a museum concept plan in October 1999, and a successful multimillion-dollar fundraising campaign was initiated under the leadership of board president Diane B. Wilsey.

The resulting design by the Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron weaves the museum into the natural environment of the park. It also provides open and light-filled spaces that facilitate and enhance the art-viewing experience. Historic elements from the former de Young, such as the sphinxes, the original palm trees, and the Pool of Enchantment, have been retained or reconstructed at the new museum. The former de Young Museum structure closed to the public on December 31, 2000. The new de Young opened on October 15, 2005.

The new museum is the fourth-most-visited art museum in North America, and the 16th-most visted in the world. Housed in a state-of-the-art, accessible, and architecturally significant facility, it provides valuable art experiences to generations of residents and visitors.

History of the Legion of Honor

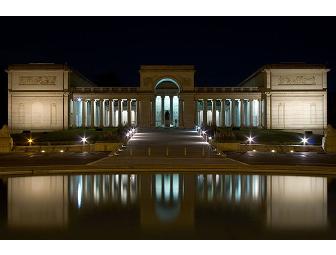

High on the headlands above the Golden Gate—where the Pacific Ocean spills into San Francisco Bay—stands the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, the gift of Alma de Bretteville Spreckels to the city of San Francisco. Located in Lincoln Park, this unique art museum is one of the great treasures in a city that boasts many riches. The museum’s spectacular setting is made even more dramatic by the imposing French neoclassical building.

In 1915 Alma Spreckels fell in love with the French Pavilion at San Francisco’s Panama Pacific International Exposition. This pavilion was a replica of the Palais de la Légion d’Honneur in Paris, one of the distinguished 18th-century landmarks on the left bank of the Seine. The Hôtel de Salm, as it was first called, was designed by Pierre Rousseau in 1782 for the Prince of Salm-Krybourg. Completed in 1788, it was not destined to serve long as a royal residence; the German prince, whose fortunes fell with the French Revolution, lived there only one year. Madame de Staël owned it briefly before Napoleon took it over in 1804 as the home of his newly established Légion d’Honneur, the order he created as a reward for civil and military merit.

Alma Spreckels persuaded her husband, sugar magnate Adolph B. Spreckels, to recapture the beauty of the pavilion as a new art museum for San Francisco. At the close of the 1915 exposition, the French government granted them permission to construct a permanent replica, but World War I delayed the groundbreaking for this ambitious project until 1921. Constructed on a remote site known as Land’s End—one of the most beautiful settings imaginable for any museum—the California Palace of the Legion of Honor was completed in 1924, and on Armistice Day of that year the doors opened to the public. In keeping with the wishes of the donors, to “honor the dead while serving the living,” it was accepted by the city of San Francisco as a museum of fine arts dedicated to the memory of the 3,600 California men who had lost their lives on the battlefields of France during World War I.

Architect George Applegarth’s design for the California Palace of the Legion of Honor was a three-quarter-scaled adaption of the 18th-century Parisian original, incorporating the most advanced ideas in museum construction. The walls were 21 inches thick, made with hollow tiles to keep temperatures even, and the heating system design eliminated aesthetically offensive radiators and cleansed the air that filtered through it with atomizers to remove dust. Seven thousand cubic yards of concrete and a million pounds of reinforcing bar went into the structure, but an assessment performed in the 1980s showed that the landmark building needed to be made seismically secure. Between March 1992 and November 1995—its seventy-first anniversary—the Legion underwent a major renovation that included seismic strengthening, building systems upgrades, restoration of historic architectural features, and an underground expansion that added 35,000 square feet. Visitor services and program facilities increased, without altering the historic façade or adversely affecting the environmental integrity of the site. The architects chosen to accomplish this challenging feat were Edward Larrabee Barnes and Mark Cavagnero.

The 1995 renovation realized a 42 percent increase in square footage, including six additional special exhibition galleries set around the pyramid skylight visible in the Legion courtyard. The glass pyramid sits atop the Rosekrans Court and special exhibition galleries located below. It is a key second focal point in a formal courtyard otherwise focused solely on Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker, as well as a light and tensile counterpoint to the heavy stone materials of the Court of Honor, lending scale and interest. The museum also provides services for scholars as well as visitors. On the lower level, the paper conservation laboratory, which is internationally recognized for its innovative and high quality work, doubled in size during the renovation. A print study room, also added during renovation, allows close examination of works on paper, as well as access to the collection by means of four computerized work stations. Similarly, a porcelain study room adjacent to the museum’s porcelain gallery gives scholars an opportunity to examine this area of the museum’s collection.

On the lower level, a spacious café provides visitors with a place to eat and relax while enjoying dramatic views of the Pacific Ocean and beyond. Across from the café, the museum store features a wide selection of art posters and books, notecards, jewelry, and other unique products inspired by the museum’s collections.